As more of my friends seemed to be getting married, I wanted to write a blog post to provide inspiration for the rest of us who are still single. But instead of appealing to feelings and stuff, we are going to appeal to basic probability.

A lot of people say that meeting people is simply a numbers game. This post will be about expanding on this line of reasoning. Whatever you are looking for at this point in life with respect to another prospective individual, let's model each interaction with that person as a Bernoulli trial with probability of success $p$. To make this concrete, let's say you are trying to get a date, and each guy/girl you approach has probability $p$ that he/she agrees to go on a date with you. We'll use this running example throughout the remainder of this post. Sure, $p$ is different for each person, but we'll make this work by setting $p$ to a conservative lower bound, and then only reaching out to people where we think our assumption holds (in other words, no going out of our league). Now we are going to make a strong assumption here, which is that the outcomes of all the people we approach are independent of one another. This means that if you ask person A out and get rejected, when you ask person B out your previous rejection by A does not affect your outcome with B. This might seem unreasonable at first, but we can sort of achieve this in real life by doing common sense things like (a) not asking the same person twice, (b) not asking friends of people who rejected us, (c) not telling someone we were rejected by all these other people, and so on.

Let's consider the following experiment: you go on an asking out rampage, and keep asking out guys/girls until you get a date, at which point you stop. We'll let $Z$ be a random variable which denotes the number of guys/girls you had to ask before you got a date, so $Z \geq 1$ by definition.

The geometric distribution, $\text{Geom}(p)$, describes the distribution of $Z$. More specifically, it tells us the probability that, given $k \geq 1$ Bernoulli trials, we will hit exactly $(k-1)$ failures followed by one success (on the $k$-th trial). It's easy to see that the probability mass function of $\text{Geom}(p)$ is given by $$ \begin{equation*} \Pr[Z = z] = (1-p)^{z-1}p \end{equation*} $$ where the support of $Z$ is $z \geq 1$. It turns out that, unsurprisingly, $\mathbb{E}[Z]=1/p$. But this is not that useful to us since we (ideally) only want to run this experiment once, whereas $\mathbb{E}[Z]$ tells us that if we were to run this experiment many times and averaged the outcomes together, we would get a number close to $1/p$ by the law of large numbers. What we really want is to know (as a sort of pessimistic person) the chance that a single experiment is going to last longer than $z$, since ultimately what we care about is the final success at the end. Using our notation, this is simply asking what $\Pr[Z > z]$ is. To derive this tail bound is simple: $$ \begin{align*} \Pr[Z > z] &= 1 - \sum\limits_{i=1}^{z} \Pr[Z=i] \\ &= 1 - \sum\limits_{i=1}^{z} (1-p)^{i-1}p \\ &= 1 - \frac{p(1-(1-p)^{z})}{1-(1-p)} \\ &= (1-p)^{z} \end{align*} $$ where the third equality comes from the formula for a geometric series. From this, we also have that $\Pr[Z \leq z] = 1 - (1-p)^{z}$. Equipped with this knowledge, let's look at some actual numbers.

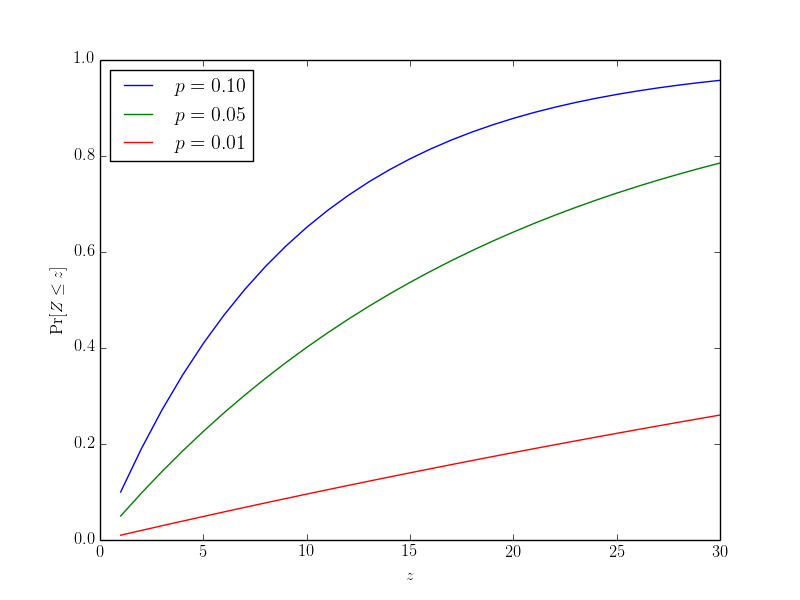

First, let's look at a graph of $\Pr[Z \leq z]$ versus $z$ for several (conservative) values of $p$. This shows that, as we increase the number of people we ask out, the chance we will succeed increases pretty fast!

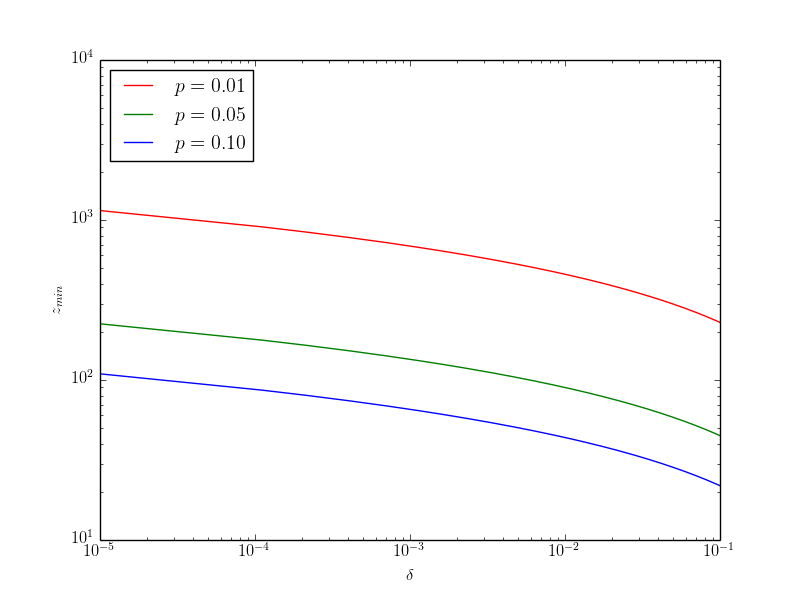

Now let's derive $z$ as a function of confidence. That is, for $\delta > 0$ we want the minimum $z$ such that $\Pr[Z \leq z] \geq 1 - \delta$. A simple calculation yields: $$ \begin{align*} \Pr[Z \leq z] = 1 - (1-p)^{z} = 1 - \delta \Rightarrow (1-p)^{z} = \delta \Rightarrow z_{min} = \frac{\log(\delta)}{\log(1-p)} \end{align*} $$ Now let's look at a plot of $z_{min}$ as a function of $\delta$

So the final takeaway is this. I'll apply these calculations to myself. I estimate that $p=0.01$ is a reasonable value for me, although I'm working to bring that up. I like 95% confidence (so $\delta=0.05$). This simple calculation tells me that if I go after roughly 298 people, I'll be 95% sure that I'll find something. But if I could bring up my $p$ to $p=0.05$, I'd only need to ask 58 people and be just as confident. Now if I were a true baller with $p=0.10$, then I'd only need to ask out 28 people!

Edit: Ryosuke Niwa pointed out a similar in spirit post here: http://en.nothingisreal.com/wiki/Why_I_Will_Never_Have_a_Girlfriend